Episode 15: Drama in the Short Story

By John Gallishaw

From Twenty Problems of the Fiction Writer

The Scene as the Unit

More and more, as you make a careful study of the modern short-story, you will become convinced that the ability to create an interesting and convincing illusion of actual life is the ability which is the mark of the highly competent craftsman. Certain Laws of Interest, as definite as the Laws of chemistry or physics, applied to your material will help you in the selection and arrangement of that material so that in presenting it you will create the illusion you wish—the illusion of actual people in actual places, reacting to stimuli in such a way that the traits or characteristics are made clear to the reader.

From a study of the Case Book you will have learned that there are four definite narrative turning points or crises in every story. One of these, the Story Situation, occurs in the Beginning; two, the Furtherances, and the Hindrances, occur in the Body; and the fourth, the conclusive act, occurs in the Ending of the story.

A glance at the chart accompanying the Lecture upon the Laws of Interest will show you that a Main or Story narrative situation (that is some feat to be accomplished or some choice to be made), even though intrinsically unimportant and uninteresting, can be made important and interesting by adding to it the promise of conflict with a difficulty; the promise of conflict with a dangerous opponent, and the promise of a conflict which will be necessary to avert disaster or defeat. When a Story situation is thus made important it contains the quality of being Dramatic. The hint or foreshadowing of difficulty, of opposition, and particularly of disaster, makes any undertaking hazardous and, therefore, Dramatic. Obviously, then, if this hint of conflict is dramatic the conflict itself must be even more dramatic. Equally, if the Promise of Disaster or Defeat is Dramatic the appearance of that Disaster or Defeat itself is even more Dramatic.

It will be apparent that just as each of the narrative turning points falls naturally into one of the three great divisions of Beginning, Body and Ending, so do these qualities of Drama. The Promise of Conflict, with difficulties, with opponents, and with impending Disaster or Defeat lends drama to the Beginning; the conflict itself lends drama to the Body, and Disaster or Defeat lends drama to the Ending. It is obvious, of course, that in every conflict there must be two opposing forces, and that necessarily Disaster or Defeat for one implies the avoidance of Disaster, (success) for the other. Thus the Ending will be dramatic if it contains either Disaster or its avoidance.

You will now begin to see that in Plotting your stories you will have to include not only Narrative interest, but Dramatic interest. From what you will learn about Setting and Actor Images, you will see that you must include also Impressions of people, places, and things to achieve the illusion of reality. In addition to Impression there is the Emotion which is Feeling, and which comes from the readers awareness of an actor responding to a stimulus.

Summed up, then, you must cause the reader to feel emotion by showing the actor’s responses in a narrative pattern of dramatic material which gives the impression of reality.

Impression will come from setting and actor images. Feeling will come from characterization. In observing and classifying material you will keep those categories in mind. Because you realize that with the short-story writer life is dynamic, you will accustom yourself to think of your material in terms of happenings.

If you see the sun rising over the Matterhorn, or if you hear a train whistling in the distance, or if the pungent odor of creosote smites your nostrils, if the breeze blows dust into your eyes on land, or salt spray into your mouth at sea, these happenings you classify as happenings which illustrate setting. If you see a stylishly dressed, tall, graceful girl of twenty, with even features and curly hair, hurrying along the street, you have observed a happening which you will classify as an image of an actor. If you see a man kicking a crippled dog or twisting a woman’s wrist, or rescuing another from drowning at the risk of his own life, or giving his last cent or his last bite of food to help a comrade in distress, you will classify these as happenings illustrating character.

Yet, on the other hand, you have not observed anything which, standing alone, contributes to that vitally necessary quality in a story which we call the Plot or the Narrative Pattern. It is important that you see this distinction clearly. A story gets its emotional value (its impression and its feeling) from Setting and from Characterization, but in its plot it deals only with narrative turning points or crises; a series of these crises properly arranged making a narrative pattern and giving it narrative or plot interest.

An important category, then, under which you must learn to classify the result of your observation is: happenings which illustrate narrative turning-points or crises.

Sometimes a happening may be made to contribute to both the emotional effect and the narrative effect, A happening which you may select as a happening illustrating setting, may perhaps also be a happening which forms a turning-point or crisis in the narrative pattern or plot. For example, a man by striking an enemy with an ax in a moment of passion illustrates his character; but this action may also be a turning point in the plot. The breaking up of the ice upon a river may illustrate setting, yet it also may be a turning point or crisis in the story of a person whose safety depends upon the stability of that ice. Herein lies the difference in attitude toward material between you, as a writer of fiction, and the writer of nonfiction. The writer of non-fiction is concerned with rendering setting and character. He sometimes is dramatic. So are you, but, while rendering setting and character you will render them as much as possible in terms of narrative and dramatic crises.

You will train your observation, therefore, to extract, wherever possible, besides impression and emotion, the narrative and dramatic value from closely linked happenings. In your presentation of your story you will always keep this in mind, and you will, whenever any element is lacking, make the additions necessary to bring about this result. As there can be no story interest until there is a narrative pattern, you will be especially receptive and perceptive toward those happenings which can be classified as contributing to the plot: as being turning points or crises having narrative quality.

As soon as you begin to think of your happenings in terms of narrative crisis you have swung out of the first phase, which is the observation of material. And as soon as you have reached the point of classification, you have begun to plot. Plotting includes, in addition to the selection and classification of material, the arrangement of the selected material into a pattern. But this arrangement comes as a result of selection and rejection. What I wish to emphasize to you now is the indisputable fact that, if you know how to observe, you can gather in one month of well-directed observation such a quantity of happenings that you will be amazed that you could ever have offered as a reason for not writing the excuse that you had nothing to write about.

It is enlightening to see what a professional writer has to say in this regard. H. G. Dwight, in Mehmish (Stamboul Nights) says:

“The fillip of life, for me, is in the small permutations and combinations of incident that make up the lives of us all. And I have often picked up a trait of character or a turn of phrase from a Mehmish that has stood me in good stead with a Pasha. Did you ever realize, however, what an art it is to tell the story of one’s day? Women sometimes have it to perfection. We call it gossip, but it is the raw material of literature, and it is better than the glum silences that fill so many habitual tete-a-tetes.”

As I pointed out to you earlier in this course, the “fillip of life” for you will be the happenings which do not seem especially worth collecting and recording to the non-fiction-writer. You may collect them from your own observation, or you may secure them from others. So long as they give the reader the impression of reality the source doesn’t matter.

This freedom of selection widens your scope of available material very greatly as you think in terms of plot or narrative interest. You will be amazed at this scope if you just run over in your mind those happenings which you can classify as crises or turning-points that you have experienced, or that you have observed, or that you have been told about, or that you have read about in the past two weeks. Here, for example, are some of the crises which apart from your own experience you may have seen, or been told about, or have read about.

- A neighbor tells you that her son, who is poor, has fallen desperately in love with a wealthy girl who has many more eligible suitors, and has sworn to win her.

- A young man tells you that he has put all his available capital into equipment for a trip to the newly discovered Canadian gold-field where he hopes to make his fortune.

- You learn from a young man, whose brother has been brutally and mysteriously murdered, that he has sworn to discover and kill the murderer.

- A woman who is hurrying for a doctor for a child who is critically ill, discovers that a railroad train will crash against an unexpected obstacle if she does not stop to warn it, thus losing precious minutes.

- A newspaper man, whose creed is that all news must be printed regardless of who suffers, is given an item telling of his son’s arrest for embezzlement.

- A prohibition agent who needs money to make good his son’s defalcation, is offered a bribe by makers of poisonous whiskey.

- A child tells you that he has been promoted in school.

- You hear that a pugilist has just knocked out an opponent.

- You read that an arctic explorer, whose ship has been nipped between ice-floes, has abandoned his expedition.

- A young man offered a bribe to betray an employer decides to remain loyal.

Now, if you will analyze these crises, you will see that they fit into different categories. The first three all show a determination to accomplish something. A young man wants to win a girl. A young man wants to make his fortune. A man wants to discover and punish an unknown murderer. The classification, then, is “some feat to be accomplished.”

The next three all show a choice to be made between courses of conduct. The woman may save the train passengers or her child. The newspaper man may suppress or publish. The prohibition agent may accept or refuse the bribe. The classification, then, is “some course to be chosen.”

As soon as you can make your readers aware of something to be accomplished or of something to be decided by an actor you have a narrative situation. (A Narrative Problem.)

Numbers 7, 8, 9 and 10 can all be classified as conclusive acts. They show that something has been brought to a conclusion. As a reading of the Case Book will show, in a story of either decision or of accomplishment, narrative turning points, or crises, then, consist of the moment when the reader becomes aware that there is some necessity for the character to accomplish some feat, or to decide between courses of conduct, and when he becomes aware that something has been brought to a conclusion of either decision or accomplishment, therefore, a conclusive act. These are narrative turning points. Until the reader is made aware that the actor must accomplish some feat or decide some purpose he is not aware of any narrative interest, or narrative problem.

The narrative problem causes the reader to ask himself a “narrative question.” As soon as the reader becomes aware of some feat to be accomplished he phrases, either consciously or subconsciously, a question: “Can the chief actor succeed in accomplishing his purpose?” As soon as the reader is made aware that the character has to choose between two or more choices of conduct, he phrases for himself a narrative question:—“What course of conduct will actor A decide upon?”

In the first case the narrative question is one of accomplishment; in the second it is one of decision. It is the narrative question which determines the narrative situation. There can be no narrative situation without a narrative question, of either accomplishment or decision.

It is quite obvious that the character’s attempt to accomplish any feat must either succeed or fail, and that eventually this must be made apparent to the reader. As soon as the reader becomes aware of this success or of this failure, his interest in that particular narrative question ceases. Equally, a person who is torn between the desirability of different courses of conduct must eventually come to some decision, even though that decision be to postpone action for the present. Sometimes this postponement is forced upon the actor by an outside force; by some other person or by some pressing immediate necessity. In effect, this decision to postpone, whether voluntary or involuntary, is conclusive as far as the necessity for decision is concerned; a course of conduct in regard to the immediate narrative situation has been decided upon definitely. The reader’s interest in that narrative question raised by that particular narrative situation ceases.

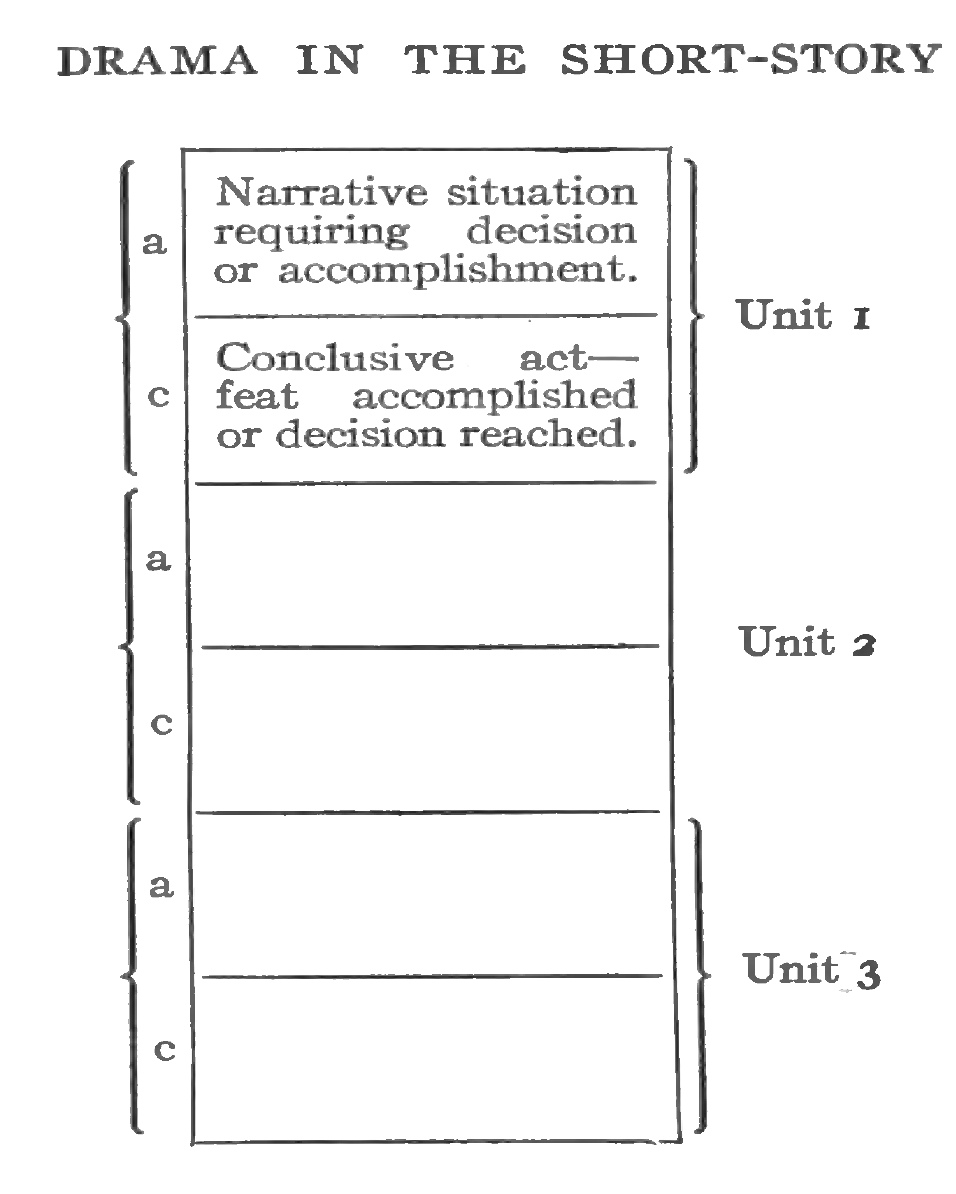

As soon as the reader is made aware that an actor’s reaction to a stimulus causes him to ask himself a narrative question, the reader’s interest is aroused. As soon as he is made aware that the narrative question is answered his interest ceases. Obviously, an outline of a story could be made up of units containing situations arousing narrative questions and of answers to those narrative questions. Sketched it would be like this:

Of course, this is a good start for the structural sketch, but there would be practically no emotional interest. There would be no sense of characters in action, and virtually no suspense; for no sooner would the reader have his curiosity aroused as to the outcome of any situation than that curiosity would be satisfied through a realization that the narrative question raised had been answered. The reader’s interest in any narrative situation will last only so long as he is unaware of the outcome of that situation. For that reason the conclusive act which makes him aware of that outcome must be delayed as long as possible if there is to be any suspense. There is only one way to delay this answer, and that is by causing the character to meet a force or forces which will either passively or actively delay or hinder the occurrence of that conclusive act of decision or accomplishment; in other words, by the introduction of other stimuli to which the character can respond. The more responses shown, the greater will be the possibility of your success in stirring the emotions of your reader.

You cannot go far in visualizing any story without seeing an actor or a number of actors in action, responding to stimuli.

Of necessity, everything an actor does or says or thinks must be that actor’s response to a stimulus. This is inescapable because everything that any actor ever does, or says, or thinks is his response or reaction to a stimulus. Thus, you see the object of observing in terms of stimuli and of response. It is axiomatic that no actor in a story can respond to a stimulus without becoming aware of that stimulus, so that basically, every character response of an actor to a stimulus is a meeting with a stimulus. Therefore, the only way to delay the answer to a narrative question is to make the reader aware of a meeting of a character with a stimulus, or stimuli, after the reader has raised that narrative question in his own consciousness, and before the reader is made aware of the conclusive act which answers for him that narrative question.

Instantly, you will have become aware of a new category into which to place the results of your observation; the category of meetings. The category of “Meetings” thus embraces three kinds of meetings. It is essential that you learn to distinguish between these kinds of meetings, because each one has its own special purpose, and for that reason I am going to ask you to employ a definite nomenclature which will enable you to avoid any difficulty of misunderstanding. For the first kind of meeting, then, the one which serves to show merely the reaction of the character to a stimulus, the stimulus not reacting upon the actor, I shall ask you to employ the term “incident.” The incident is the single act of a single actor reacting to a stimulus, which is itself inactive to the extent of having no design upon the character, thus: “at the stroke of five John Morton laid down his pen.” The stimulus is the condition of five o’clock striking. The reaction of John Morton is to lay down his pen. In the meeting which we shall hereafter classify as an incident there is no interchange between the stimulus and the actor. The actor alone is responding. That is to say, he reacts; the stimulus does not react. As soon as there is an interchange, there is a meeting of another kind. For example, “Upon the stroke of five, John Morton, noticing that his friend and fellow-worker, Bob England, was still bent over his ledger, walked across the office and whispered under his breath”Come on, old boy, the tocsin has sounded." “Right you are,” his friend responded cheerfully, “I’ll just put these books in the safe and be with you in half a minute.”

In this type of meeting, two forces meet amicably; there is an interchange without clash, each force forming the stimulus to which the other responds, and each one actively and designedly reacting upon the other. John Morton responds to the sight of Bob England; that response itself becomes the stimulus to which England’s speech forms the response. For the purpose of mutual and definite understanding between instructor and instructed, we shall hereafter in talking about this type of meeting of two forces involving “interchange without clash”—employ the technical term “episode.”

There is another type of meeting in which two forces meet, but in which the interchange involves clash or conflict. If John Morton crosses to his friend Bob England and suggests that the two go out, only to find that England is irritable and gruff, and is himself roused to retort, then there is a meeting with clash, both forces being stimulated by the action of the other. To describe such a meeting we shall employ the technical term “encounter,” which is a meeting of two forces, both actively reacting, with clash.

There are, therefore, three kinds of meetings, the incident, the episode and the encounter.

- The incident is the single act of a single force; it may present either a stimulus or a response. “As soon as he spied the policeman Henry tiptoed across the street” is an incident; it is the single act of a single force. The force is Henry, the act is his tiptoeing across the street. It shows his response to a stimulus, which is the sight of the policeman. That stimulus is presented as an incident. “He (Henry) spied the policeman.”

- The episode is the meeting of two forces without clash; thus: “As soon as he spied the policeman, Henry tiptoed across the street, and coming up behind the officer, tapped him lightly on the shoulder. “The other swung around sharply, his hand reaching instinctively for his hip pocket. “At the sight of Henry he relaxed: ‘Yuh frightened me fer a minute’ he said. “Henry leaned close ‘I’m going up the street for about two minutes. Keep your eye on the door of that garage, and if anybody comes out, blow your whistle.’ “The policeman nodded understandingly. ‘Don’t be long’ he said. ‘There may be something doing any minute now’.”

- The encounter is the meeting of two forces, with clash; thus: “As the moon rose slowly above the low roof of the garage, Henry could see the policeman crouching in the angle between two buildings. The officer’s back was turned, and his gaze was fixed upon the door of No. 29. Tiptoeing with infinite caution, Henry crept up behind him. He was almost upon the bulky figure when the policeman, apparently satisfied by his scrutiny, turned around without haste. At the sight of Henry he stiffened, his hand reaching instinctively for the revolver in his hip pocket. Even after he had recognized Henry he did not change his attitude. “ ‘Don’t get excited,’ said Henry, I’m just going up the street a minute.’ “The policeman continued to gaze at Henry coldly. ‘You are not/ he said. “ ‘Why?’ inquired Henry. “ ‘Because I got me orders that nobody leaves this alley before the Chief gets here.’ “ ‘Good heavens’ said Henry, in annoyance, ‘that didn’t include newspaper men.’ “ ‘It goes for everybody,’ said the other shortly. “ ‘What’ll you do if I go ahead?’ “ ‘Try it and see,’ said the policeman, and continued to regard Henry without smiling. When he saw that Henry had apparently no intention of retreating he produced the ugly looking automatic, and pointing it at Henry’s stomach, said meaningly, ‘Get back where yuh came from, and if yuh make a sound, I’ll plug yuh.’ “It was clear to Henry that the officer meant what he said. There was no profit, he thought, in being shot; so he stepped back, gingerly, to the place he had left.”

You are now in a position to add to your sketch of the presentation unit, some clarifying information, by placing after the word Meeting, the explanatory words incident, episode or encounter. The incident is the irreducible minimum. Perhaps the most enlightening instruction a teacher of short-story craftsmanship could ever give is to drill into those people who have difficulty in developing material the comprehension of the basic importance of the incident. Every time you render for your reader an account of a force in action you have begun to write a story. Plotting consists merely of putting that incident into its proper category. It is a simple thing to record an incident to be used in a Story, because it involves merely showing an actor responding to a stimulus, that stimulus being another actor.

You may build that incident up until it becomes an episode by causing the response of the first actor to form the stimulus to which a second actor responds; and the episode may be expanded to the extent to which you keep up the friendly interchange or interaction. Always, however, it will be by the addition of more incidents.

Just as it is possible to build up an incident into an episode, by the addition of other properly selected incidents, so is it possible to build up an episode into an encounter, by the addition of further incidents introduced to show that hostility has entered into the interchange. The incident is always the lowest common denominator.

Arranging incidents so that they form episodes presents no problem. Adding clash to such episodes to produce encounters is comparatively simple; it demands only the most elementary knowledge of craftsmanship; even the mediocre writers do it instinctively. By adding clash they manage to add dramatic effect, but they could keep on doing so forever and they would not achieve narrative or plot interest.

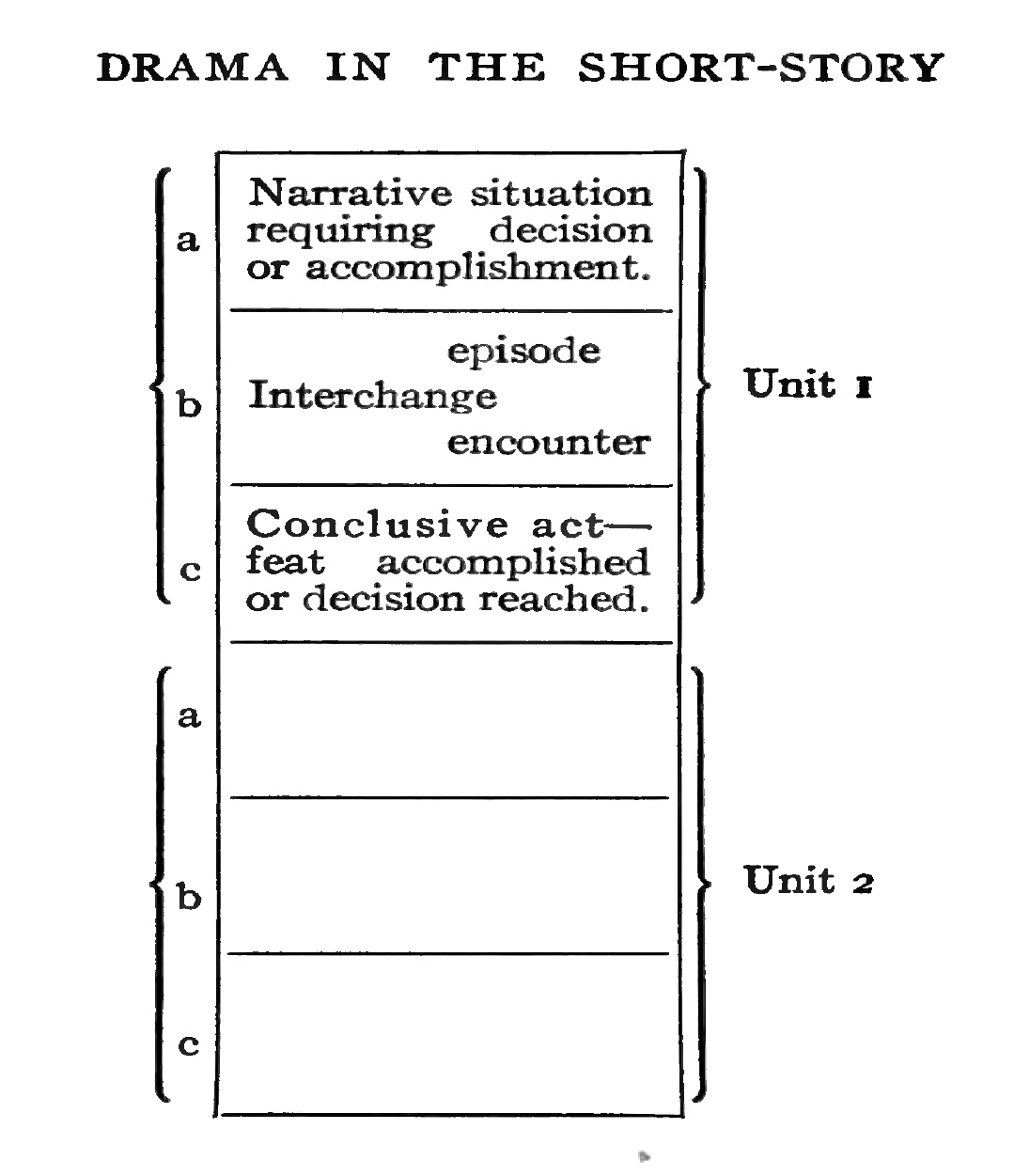

Narrative or plot interest is contributed to any meeting within the story in the same way that narrative interest is contributed *to the story as a whole*—by preceding the meeting by its own situation and following it by its own conclusive act. This structural unit of situation—meeting—conclusive act—we shall call a “Scene.” A unit within the story, it has exactly the same functional divisions as the whole story.

- The raising of a scene narrative question to capture the reader’s interest by making him aware of a scene situation.

- The delaying of the answer to that scene narrative question through the readers’ interest in the interchange which follows.

- The answering of the scene narrative question raised, in such a way that there is no longer any doubt in the reader’s mind as to the outcome of the interchange.

It is the second of these divisions within the scene which at the present moment concerns you most closely. It may be an incident, an episode, or it may be an encounter. It is so unlikely to be an incident that you can afford to ignore an incident as a possibility for your consideration and narrow down your investigation to the episode and the encounter. Each of the “scene” units that make up the story, you can say with assurance, has the same functions as the complete story, and it has, like the complete story, a Beginning, a Body and an Ending, corresponding to the functional divisions of situation, interchange, conclusive act; the interchange being the Body.

The unit of structure which I sketched for you, now becomes enlarged by the interpolation of another subdivision, and sketched, looks like this:

It is the interchange within this scene unit to which you must devote your best efforts. Upon your ability to present it interestingly and convincingly you must eventually stand or fall. You must, if you are to be successful, apply to it the Laws of Interest. An interchange, you know, may be either an episode or an encounter. But, if it is an episode it cannot be dramatic, because an episode has no clash. It cannot be narrative because if there is no clash there can be no alternation of Furtherance and Hindrance, and, therefore, no uncertainty. As soon as you add clash to the interchange you almost inevitably add alternation of Furtherance and Hindrance. As soon as you add Furtherance and Hindrance to the interchange you achieve clash. Thus drama adds narrative and narrative adds drama. But as soon as you add drama, which in the Body is conflict or clash, you change the episode to an encounter. Thus we see that the Body of the narrative unit within the story, which we shall hereafter refer to as a scene, may be either episodic (if it has no conflict or clash), or dramatic (if it has conflict or clash). We now can draw some very definite conclusions that will go far in clarifying your task.

First. There are two kinds of situations—Story situations and Scene situations.

Second. The Story situation (the main situation) projects the actor into a series of attempts or interchanges, each one having its own scene situation or purpose.

Third. A Scene situation is followed by a single attempt or interchange. Thus, a man’s purpose to win a girl would form a story situation. In the course of his attempts to win the girl, the man might need two hundred dollars. His purpose to borrow the two hundred dollars would form the scene situation.

Fourth. The Body of a scene may be an episode. In that case the scene is an episode scene.

Fifth. The Body of a scene may be an encounter. In that case the scene is a dramatic scene.

Sixth. The incident (the single act of a single force) is the basic structural unit. It may be expanded gradually into

- episode

- encounter

- episodic scene

- dramatic scene

- complete story

The dramatic scene contains all the elements of the complete story. It is a miniature short-story. The complete story is made up of the number of these scenes. Clearly, then, if every story consists of a number of scenes, in order to be able to write a short-story you must first be able to

- Distinguish between Story situations and Scene situations.

- Build up an incident through its different phases until it becomes a dramatic scene.

- Present the dramatic scenes convincingly, so that the characters of the actors emerge against an impression of Time and Place.

Throughout each dramatic scene, through the actor’s reaction to different stimuli, you will make his character clear to your reader. The technical devices for illustrating character you will become familiar with from your study of the Lecture on Characterization. In the long run, you must realize that characterization is everything in a story, and that your real reason for familiarizing yourself with structural devices is to acquire complete control of methods in order that you may not be hampered in rendering character through the medium of the Modern Short-Story.

The chief aim of this course is to teach you the fundamental architectural conception of a short-story as a series of blocks, each block being the equivalent of a scene. However, since no architectural conception of a story will of itself produce a story, there must be, within that architectural conception, the breath of life which comes from characterization of actors responding to stimuli.

The value to you of knowing just what is a scene is inestimable. It is a smaller unit than the complete story, yet in architectural conception it is the same. Being the same in essence as the complete story, the dramatic scene gives you opportunity for developing your plotting ability as well as your presentation ability. It includes:

An impression of Time and Place, and Social Atmosphere.

An impression of an actor’s appearance.

An impression of the stimuli to which the actor responds.

Since the largest number of your scenes will be scenes in which the opposition to an actor is furnished by another actor, the second actor and his responses will be the stimuli to which the first one will respond. Therefore, the first step in a dramatic scene of that kind is to bring the two actors together— To achieve narrative interest you show your reader that one of the actors has a purpose (we shall leave for later consideration the scene requiring choice). To achieve dramatic interest you show your reader that the other actor is opposed to that purpose. So far you are dealing with the Beginning of the narrative scene. In plotting it you will keep in mind that the purpose of actor A may bring about the meeting with Actor B. For example, if A wants to borrow ten dollars from Actor B he may go to actor B’s house or office to meet him. On the other hand, actor A may not think of attempting to persuade B to lend him ten dollars until after he has run into Actor B casually on the street. In this case the purpose grows out of the meeting; in the other case the meeting grew out of the purpose. That is entirely a matter of choice with you as author, depending upon your conception of how things would have happened in real life.

In plotting and presenting a dramatic scene, remember that your detail must give the impression of reproducing real life. In giving your actor a purpose, be sure to reproduce the ordinary purposes which actuate people on every hand. In that way you will achieve verisimilitude, or the appearance of truth. You will find as you observe closely that when one actor meets another his purpose is to secure information; to convince the other of something the other is doubtful about; to persuade the other to adopt a course of conduct; to impress the other with his own importance or lack of importance (if he is trying to evade a tax, for example). As soon as such a purpose appears, the reader is caused to ask himself a scene-narrative-question.

Can Actor A secure information from Actor B?

Can Actor A convince Actor B?

Can Actor A persuade Actor B to adopt a course of conduct?

Can Actor A impress Actor B?

When there is physical clash, the reader asks himself, “Can Actor A overcome Actor B or Force B?” Once you have enlisted the narrative interest of the reader in the purpose of an actor in a scene, and have added dramatic interest by the hint of conflict, which will come in the interchange between the chief actor and the opposing actor, you must take swift advantage of that interest to present the interchange in such a way that the outcome of the actor’s attempt to achieve his purpose is in suspense. Every speech or act of Actor A will be intended to accomplish his object. If this attempt promises success, there is a Furtherance of the Scene-narrative-question.

If from a year’s study of this course you mastered nothing but the fact that every attempt of an actor to bring about a narrative purpose is a Furtherance to the purpose and to the scene narrative question raised in the mind of the reader by the knowledge of that purpose, it would be a year well spent, provided you coupled with it the knowledge that the furtherances are introduced to give plausibility to the Hindrances which give the dramatic interest through their promise of ultimate disaster or defeat.

Therefore, to ensure a dramatic scene you must be sure to follow every Furtherance (that is, every attempt of an actor to bring about his immediate purpose in that scene) with a Hindrance. To do this you will show the opposing actor attempting, by his speech or act, to prevent the chief actor from accomplishing his purpose. If this attempt promises failure for the chief actor in that immediate purpose, there is a Hindrance to the Scene narrative question. This interchange between Character A and Character B will, in the well balanced scene, occupy the largest proportion of the space.

Finally, in completing the scene you will show the conclusive act of the scene which brings the interchange to a close. This conclusive act will show that the actor whose purpose raised the scene narrative question has either abandoned his purpose or achieved his purpose. It will be either Defeat or its avoidance. The answer to the Scene narrative question will be either Yes or No. It can never be “perhaps,” because even though the encounter between Actor A and Actor B results in a draw, it is a defeat for Actor A. He has not achieved his purpose.

Keeping in mind the analogy between the scene and the story, you will add whatever significance there may be as a result of the encounter:

- As it affects the Character. For example: “Although victorious, he felt strangely dissatisfied.”

- As it affects the Opposing Force. For example: “He glared at Thompson from the corner into which he had been thrown. It was apparent that, although defeated, he was not conquered.”

I shall say nothing at the moment about the relation of this step in the scene to the main narrative problem of the story. I shall leave that until we deal, later, with the general problem of plotting the story as opposed to plotting the scene. It is sufficient for you to remember now that the first rate modern short-story is made up of a number of dramatic scenes. Clearly, then, this being the case, in order to be able to write a short story, you must first be able to plot and write good dramatic scenes.

As soon as a writer has mastered the problem of enlarging encounters into scenes he has achieved narrative interest. Perhaps it would simplify this if I were to say that the problem is one of enlarging meetings into scenes. Narrative interest is added to any meeting by preceding the interchange by a scene purpose showing that the response of an actor to a stimulus is the determination of the actor to accomplish something, and by following this interchange with a conclusive act. The actor whose purpose gives the scene its narrative interest may be any actor in the story. There are, therefore, the following steps to each scene:

- To bring actor and opposing force together

- To show that one has a purpose

- To show interchange

- To show conclusive act

- The effect. (By this step you tie your scenes together into a story.)

The fifth step sometimes appears to be missing. This is frequently because there is so much of it that it forms by itself another complete scene. An actor in one scene may have failed to secure a loan of ten dollars. The fifth step may consist of his reflections that he was unwise to ask. It may consist of a visit to another person whom he tries to persuade to give him a job. This visit will itself form another scene.